Project Flesh

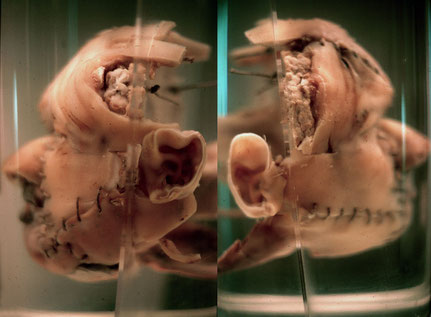

This project addresses one of the main problems of sculpture, namely its medium. Opting for the hyperrealist approach, and drawing on works by George Segal, Duane Hanson and Ron Mueck, I set out to make sculpture that would be as faithful to the model as possible. This is how it became evident to me that I should use meat. (Even if the sculptures are not perfect renditions of the model.) Sculptures are usually created from materials that bear no resemblance to human flesh (i.e., stone, wood, etc.), whereas I have used material very similar to human skin: pork. First, it is an extreme approach to the Aristotelian mimetic theory of art; second, an interpretation of the definition of the scientific model;

Vagina Refreshing

PLASTINATION ( a process involving fixation and dehydration and forced

impregnation and hardening of biological tissues; water and lipids are

replaced by curable polymers (silicone or epoxy or polyester) that are

subsequently hardened; "the plastination of specimens is valuable for

research and teaching")

Form of Sex

The Hungarian FHM got in touch with me. A magazine that men buy to masturbate over naked women and expensive cars. Half a page is always reserved for “art”, for instance the artist painting

with shit, the world’s greatest pumpkin carver and the like. They were asking for pictures of my work and I refused them thinking they do not in any way represent a platform of exposure for me.

In the end, they did manage to get hold of some and the article was published. A paper in which the climax is represented by a vagina peeking out did not dare show my “flesh-vagina” sculptures,

only the “blow-job” one (using it merely as an excuse to express their homophobia). So that’s what the Flesh Project is about.

Actions

Exhibitions

Organs and Ecstasy

Carne Trémula

First blood

Vam Design Art project

Q&A - In reference to the Project Flesh

Richard Mauger: In using meat it is almost impossible for the viewer to have an emotionally detached reaction to the pieces. Is this something that you like about the medium?

Géza Szöllősi: I don’t generate the effect evoked by my sculptures, the flesh does. Essentially, they can be regarded as Duschamp-type ready-mades, where the original object carries the whole

show. On one hand, there exists a sex centred attitude, further amplified by the mass media, which is solely obsessed with the body and regards people as mere objects, on the other, we live in a

prudish world, that’s rooted in Christianity, struggling with a sense of guilt and revulsion against the human body. Because of the latter our society turns away from where it can sense the smell

of death. As there is a cult of body building in terms of sports, diet and fashion, to the same extent the opposite of these are considered taboo. Why? According to Hermann Nitsch, facing the

reality of flesh is one of the fundamental conflicts of human existence and, since direct engagement with the flesh has become a taboo, our sensory reactions to it are particularly intense due

precisely to its being a taboo.

What inspires you to create certain parts of the body in isolation?

There is one simple reason for this. The technique. Everything else apart from faces and the genitals is too complex to be sewn “nicely” together using inanimate flesh. As a result of this the story developed in the way it did. Technique influenced content and vice versa... If it’s genitalia, it’s women, if it’s women it’s the loved ones. Now the loved ones are gone.

What is it that drives you to explore the human form in such depth through this type of sculpture?

What’s written above applies to me too. I admire the pictures of bodies and feel repulsed by the sight of my own and other people’s bodies if they do not reach a certain aesthetic standard determined by others.

In creating works from constructed flesh it takes the sculptures one step closer to reality which inevitably causes it to take on a controversial nature, how do you feel about this?

The inner contradiction of flesh constructs lies in the fact that the deceivingly faithful simulacra, which in essence are made of the material of their imitated originals, paradoxically are only as repulsive as the “original” human ones.

A true “natura morta”, where dead nature is reborn in a different form.

Does the work from the Flesh Project share many of the same ideas or inspirational origins as the Prayer Mats pieces?

I look for means in our culture.

With a small trick (that is “art”) I cause a self explanatory object run into a contradiction with itself.

Relics

Péter Márta a Test Víziók-konferenciáról

...

És az utóbbi állításnak részben máris ellent kell mondanom, hiszen a kétnapos stúdium (február 26–27.) első művész előadója Szöllősi Géza volt, aki Hús projekt sorozatában emberformáit (is) állati húsokból, szövetekből-bőrből-szőrből formázza meg. Hogy ez miképpen történik, milyen tárgyi eszközök és konzerváló anyagok szükségesek a művelethez, azt egzakt módon összefoglalta, és vetített képekkel is illusztrálta. A formalinos megoldáson túl a szobrászati szempontbél kívánatosabb, ám némileg bonyolultabb száraz tartósítást, vagyis a plasztinációt alkalmazva hozza létre – az ismertetőben hivatkozott Otto M. Urban szerint – „kísérteties", a nekrofília jelenségére „közvetlen utalást tevő" kreációit. Annyi biztos, hogy a plasztináció eljárását kidolgozó heidelbergi orvos „alkotási" kedvének eredménye, az első nevezetes Emberi Test-kiállítás minden döbbenetes fizikai és mentális aspektusával háttérbe szorul Szöllősi individuális teremtményeivel szemben, „akiket" megalkotójuk még személyesebbé avat azzal, hogy sokszor maga is behajol a képbe. E fotókon szájával közelít az állati húsból durva öltésekkel varrt archoz vagy vaginához, esetleg hasonló módon kreált péniszt dug az állathús női szájba vagy épp vaginába. Ahogy előadásában mondta: „egykori szerelmeim, akik elhagytak, így megőrződnek" – más kérdés, hogy erre a művészi „hagyatékra" ki hogy tekint, rácsodálkozik-e, hogy a feje vagy nemesebb testrésze miképp fest pacalban, disznóhúsban, netán könnyen használható kakasbőrben... Pláne, ha ismeri az alkotó azon véleményét is, hogy „egy ilyen szobor csak annyira taszító, mint az eredeti lehetne". Ám Szöllősi azt tartja magáról, hogy ily módon „arcokat és genitáliákat képes készíteni, a kéz túl bonyolult, az egész test túl nagy". Minden technikának, eljárásmódnak megvannak tehát a maga korlátai, különösen a nyersanyagként eleve romlékony húsnak, amellyel csak néhány napig lehet dolgozni.

Büféasztal spagetti-csontváza

Szöllősi nem kerülte meg témájának különféle aspektusait, kényes pontjait sem, beszélt az alkotó modellel szembeni hatalmi helyzetéről, arról, hogy a húsnál a szexualitás megkerülhetetlen, sőt, érintette a pornográfiába való belépés szükségszerűségét is, kifejtette, hogy a szobornak a hús miatt jelenléte van, beszélt az embe-rek ellentmondásos viszonyulásáról, mert részint a szobrok hús alapanyaga miatt elfogadóbbak, ám ugyanezért „nem tudnak megszabadulni attól, hogy a látvány egy személy", ám ahogy mondta, „ezek a szobrok a személy halott állapotát testesítik meg". Elmondása szerint bosszantotta, hogy a kiállításai kapcsán olykor a személyével is foglalkoztak. Utóbbi dolgon azonban nincs mit csodálkozni, hiszen az alkotó sohasem független az alkotásától, ahhoz mindenkor és minden értelemben mély köze van. És hiába, hogy a konyhákban sokszor vagdosnak húsokat, nem mindegy, hogy pörkölt vagy szobor lesz belőle. Tehát olykor nem is az anyag, hanem a szokatlan összefüggés gerjeszthet furcsa, bizarr kérdéseket. Ahogyan egy kórházi sebészeten is sajátos árnyalatot kapott az orvosi szobán olvasható név: Dr. Hentes. Az áthallásoktól nem lehet szabadulni, csak ha az ember steril, programozható géppé tárgyiasul. Ebben a vetületben még az sem mindegy, hogy közvetlenül, fizikai valóságában szemlélünk valamit, vagy a filmvásznon. Szöllősi ugyanis a Taxidermia és az Ópium című filmek special art design munkái révén robbant be a köztudatba. A filmre írt szürreáliák befogadásának/megélésének pszichológiája azonban némileg eltér a kiállított hús-kompozícióétól, amelyben leginkább a brutális realitás hat az érzékekre. Ugyanakkor ezek a plasztikai struktúrák mégsem reálisak, hiszen más lény valódi húsában mutatják meg a jelen nem lévő és halottnak tételezett húst, azzal a „kis" csúszással, hogy itt nem a modell, vagyis az ábrázolt alany, hanem az annak anyagául választott állat, illetve húsa a halott. Vagyis a Hús projekt darabjai a valónál többek és kevesebbek is. Bizonyos értelemben talán lentebbiek, mert már száműződött belőlük az, amihez az emberi lénynek elsőrendűen köze volt/lenne, amiért embernek teremtődött. Úgy tűnik, Szőllősi húsműveinek drámája ebben a hiányban fogható meg, s hozadékuk épp e hiányra döbbenés lehet – akár az alkotói szándék ellenére. Miközben a szobrász fontos művészet- és társadalomelméleti összefüggésekbe ágyazta saját útját, és utalt rá, hogy külföldön már megteremtődött a rossz közérzet és horror kultúrájának posztmodern hagyománya a testábrázolásban, jelezte, hogy a nézők nehezebben emésztik meg a provokatív-sokkoló hatást, ha az műtárgyként exponálódik. Igen. Szöllősi becsülendő önreflexiója szerint: „a sorozat, az egész projekt egy kudarc".

(2015. szeptember)

Decadence Now!

Vision of Excess

Group exhibition /curated by Otto M. Urban/ Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague, 2010

The Decadence Now! is the international exhibition project of its kind which attempts to conceptually work with the concept of decadence in current art. The exhibition is not divided chronologically, but thematically into sequential sections which fluently and logically relate to each other, and which also create a sort-of imaginary closing circle.

Parts of the exhibition:

Excess of the Self: Pain

Matthew Barney, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, Gilbert & George, Gottfried Helnwein, Damien Hirst, Jürgen Klauke, Robert Mapplethorpe, Yasumasa Morimura, Catherine Opie, Pierre et Gilles, Cindy Sherman, Andreas Sterzing, Joel-Peter Witkin, David Wojnarowicz

Excess of the Body: Sex

Nobuyoshi Araki, Marc Bijl, Wim Delvoye, Martin Gerboc, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Jeff Koons, Niba, ORLAN, Jan van Oost, Pierre et Gilles, Andres Serrano, Cindy Sherman, Géza Szöllősi, Tsang Kin-Wah, Joel-Peter Witkin

Excess of the Beauty: Pop

Boaz Arad, Ondřej Brody, Jiří Černický, David Černý, Gilbert & George, Martin Gerboc, Gottfried Helnwein, Zsófia Keresztes, Nick Knight, Alexander Kosolapov, David LaChapelle, Zbigniew Libera, Alexander McQueen, Robert Miller, Yasumasa Morimura, NIBA, Shimon Okshteyn, Erwin Olaf, ORLAN, Pierre et Gilles, Jamie Reid, Terry Rodgers,

Comenius Roethlisberger, Paolo Schmidlin, Richard Stipl, Géza Szöllősi, Mark Ther, Maciej Toporowicz, Joel-Peter Witkin

Excess of the Mind: Madness

David Bailey & Damien Hirst, Matthew Barney, Josef Bolf, Gottfried Helnwein, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Jürgen Klauke, Joachim Luetke, Ikuko Miyazaki, Yasumasa Morimura, Catherine Opie, Zhang Peng, Joel-Peter Witkin

Excess of the Life: Death

Steven Gregory, Keith Haring, Damien Hirst, Václav Jirásek, Robert Mapplethorpe, Jan van Oost, Ivan Pinkava, Joel-Peter Witkin

Project Flesh in Decadence Now!

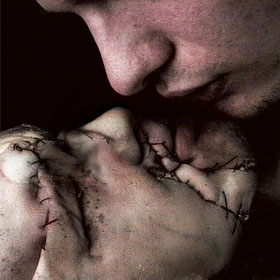

His method, or its use, however, is closer to the scientific experiments of Dr. Frankenstein. In his cycle Flesh Project, Szöllősi created female torsos by aligning the flesh and skin of animals. The rough stiches refer back to the autopsy table. Flash Project thus attains a more than macabre character, as it makes direct allusion to the phenomenon of necrophilia. The motif of a man-made creature whose primary role is to fullfil the function of a sexual object appeared throughout the 20th century. There is the notorious instance of Oskar Kokoschka, who for sometime after his separation from Alma Mahler lived in the company of an artificial doll designed to remind him of and to replace his ex-lover. Equally notorious are Hans Bellmer's Poupees, which in turn caused many other artists to gravitate towards the subject. Most frequently mentioned in this context is the American artist Cindy Sherman, in particular her cycle Sex Pictures (1992).In this cycle the artist herself completely vanishes from her images, instead working exclusively with artificial mutant torsos of human forms. (…)

Otto M. Urban: Decadence Now! Visions of Excess,

Arbor Vitae publishing, 2010, Prague, pp. 126-127

Interview

Catalogue of Decadence Now!

My Loves

“Yet each man kills the thing he loves,

By each let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

Some kill their love when they are young,

And some when they are old;

Some strangle with the hands of Lust,

Some with the hands of Gold:

The kindest use a knife, because

The dead so soon grow cold.

Some love too little, some too long,

Some sell, and others buy;

Some do the deed with many tears,

And some without a sigh:

For each man kills the thing he loves,

Yet each man does not die.”

Oscar Wilde

This art is mainly about the body. The artist wanted to depict the body as true to the original as possible, and to achieve that, he used pork flesh.

Clever.

Obviously the pork flesh he is using has to be dead prior to sculpting, and as a result, the sculptures seem more like corpses than live bodies. Something that also enhance this quality about the work is how the bodies are brutally stitched up and divided into parts. The artist, being a man, has chosen women as his subjects, and it comes as no surprise what sort of "parts" of them he has chosen for the base of his work.

As if showing pork flesh vaginas isn't enough, he then gets intimate with his flesh creations. associations of women seen as meat and objects comes to mind (not to mention necrophilia).

It's just that in our society, the body is always female, and the eye that sees belongs to a man. Unless it's a male body being seen by a homosexual man. This is nearly the only case where a male body is objectified. if you see porn with cocks and naked men, or even art with naked men, it is nearly always labeled

"homosexual". I want to claim the right for women not to see through the eyes of a man, but through their own, and have what they see acknowledged by all as equally important.

There's nothing wrong with the body being an object, it's an aspect of it's existence. but I don't like the notion of female bodies (and thus myself) as MORE of an object, closer to nature and animal, than the male body. I refuse to identify with these flesh sculptures as they remind me of this absurd untruth.

http://chainsawpixiepuff.blogspot.com

Portraits

My Father, 2002, animal flesh

Self portrait, 2004, animal flesh

Yuka from Japan, 2007, animal flesh, formaldehyde

Selportrait, 2010, animal flesh

Nemes Z Márió: Budapest Horror

A hús és a szerves anyagok képzőművészeti hasznosítása a hatvanas-hetvenes évek performansz-művészeti és body-art munkáiban kezdett elfogadott gyakorlattá válni. Mindenekelőtt Herman Nitsch O. M. Színházát érdemes megemlíteni, ahol az állati hús széttépésének rituáléja az előadások fontos részét képezi. Magyar kontextusban Lovas Ilona marhabél-installációit lehetne kiemelni, melyekben a bél felnyitása és felmutatása egy transzcendens titok belsejébe vezeti el a nézőt. Lovas és Nitsch egyaránt a szakrális metaforika felől gondolják el a hús szerepét a műalkotásban, ezzel egyfajta evidencia-médiummá avatják a testiséget, vagyis ereklyét csinálnak a biológiai rekvizitumból. Ezzel a poétikával szemben Szöllősitől idegen mindenféle szakralizáció, vagyis a hús nála nem szellemül át valamilyen transzcendencia irányában, amitől csak még obszcénabbá válik a hús-szobrok „antropomorfizációja”. Szöllősi művészetéhez közelebb áll Damien Hirst preparációs-eljárása, azzal a különbséggel, hogy míg Hirst művei az orvosi-metafizikus tekintet sterilitását imitálják, addig Szöllősi munkáiban mindig megmarad egyfajta pszeudo-vallomásosság.

A Hús-projekt egy disznóhúsból készített önarcképpel indul. A megformálás lényege a kísérteties „hasonlóság” megképződése. A hasonlóság azért lesz ambivalens, mert a művész egy nyilvánvalóan mesterséges fejet készített (az összevarrás, a megcsinálás jelei kihangsúlyozódnak), ugyanakkor ez a fej nem fiktív – a „valótlanság” értelmében – hiszen a hús érzéki közössége köti össze az emberi fejet és az önarcképet. A fej kísértetiessége vizuális határsértés, mely összezavarja nemcsak a kép-tapasztalatot, hanem a test-tapasztalatot is. A hússzobor nem élő test, de nem is annak halott mása, amire utal, hanem hibrid képződmény, mely a hasonlóság romjaiból születik. Talán közelebb jutunk a kérdés megoldásához, ha felidézzük Jean-Luc Nancy-nak a portré működéséről írott gondolatait. A francia filozófus szerint a portré az arc mindenféle utánzásával egy viszonyt hoz létre bensőség és külsőség között, vagyis a képi megjelenítés külsőlegességében ex-ponál (nem ábrázol, hanem létrehoz) egy szubjektumot. Emiatt van az, hogy a meztelenség sohasem lehet a portré része, ugyanis: „Bármilyen kapcsolatban is álljon egy meztelen test egy arccal, a meztelenség olyan kérdést vet fel, amely nem a szubjektum kérdése, vagy nem kizárólag az, mivel a kérdés ekkor már nem a „személy”, hanem a meztelenség önmagáért (még ha az egy személy meztelensége is).” Szöllősi önarcképében a hús pőre anyagisága a meztelenséghez hasonlóan működik – vagyis megtöri a szubjektum exponálódását, és visszaveti a nézőt az Én előtti személyesség „senkiföldjére”. A befogadó megpróbálja antropomorfizálni és megszemélyesíteni az anyagot, de ez a folyamat megfeleltetések képlékeny rendszerét eredményezi, mert a hús eredendő formátlansága nem engedi „igazi” személlyé-emberré válni a fejet.

Mintha a művészeti produkció arra törekedne, hogy ebből a formátlanságból végre valami szilárdat termeljen ki és tartósítson. Ez a szentimentális hangoltság a preparátori indulat eredője. A Hús-projekt Győrffy László Agytörmelékeihez hasonlóan személytelenül személyes antropológiai múzeum, melyben egy „meghaladott” emberi világ romjai láthatóak. A szentimentális preparátor nem tud elszakadni az antropológiai töredékektől, mert ezek jelentik számára az otthon és a múlt ígéretét, hiszen bármilyen poszthumanizmus is csak egyfajta emlékezetmunkával – reflexív idézéssel – tudja újraírni az ember fogalmát. Az eredmény kevert állagú világ, melyben emlékezés és felejtés viszonymozgása által egy hiányos családtörténet jelenítődik meg (vö. Apám arcképe, 2004, Nagyanyám bal lába egy félcipőben, 2005). A hússzobrok ennek az elbeszélésnek a privát totemei. Ahogy a törzsi tudat számára a totem az ember és állati között közvetítő entitás, úgy a hússzobrok is kettős helyet foglalnak el. „Valami” állatiból készültek, és „valami” emberit formáznak, vagyis megnyitják az utat a két szféra közti kölcsönös létesüléseknek. A családtörténet magában a húsban mint világszövetben bonyolódik, ahol egymásba ágyazódnak a szervesség különböző szintjei. Apánk toteme disznóhúsból épül, de ez nemcsak a két létező naiv azonosítását jelenti, hanem azt is, hogy valójában nem tudjuk pontosan milyen „állagú” családunk és kultúránk, nem tudjuk milyen anyagot találunk majd a kutatás végén. A szervesség végül is feneketlen, akár az ember.

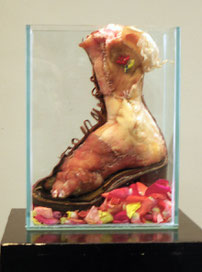

A Hús-projekt talán legprovokatívabb részét a Szerelmeim című sorozat (2003-2007) darabjai alkotják. A Szerelmeimben Szőllősi női szeméremtesteket „épít”, melyeket karakterizál és egyénít is, hiszen fotókat, hajcsatokat, játékbabákat „egy konstruált barátnő pszeudoperszonális kellékeit” (Győrffy László) applikálja a hússzobrokba. A Szerelmeim a családtörténet kitágításaként értelmezhető, hiszen a korábbi poszthumán szentimentális jellemzi ezeket a műveket is. A legnyilvánvalóbb művészettörténeti példaként Gustave Courbet A világ eredete (1866) című képe kínálkozik, mely egy melltől combközépig kitakart női akt. Vagyis Courbet még egységes emberi alakban gondolkodik (hiszen nem nemi szervet fest, hanem egy akt részletét!), de ezt az egységet a maga érzékiségében akarja feltárni – és uralni, hiszen a kép a maszkulin zseni diadala, aki a nemi szerven keresztül az egész nőt és az egész világot uralja. Szöllősinél egy antropológiai átíródás megy végbe, mert a vagina-szobrokban a világ és az ember eredete de-centralizálódik: kimozdul a test „alól”. Ezek az antropológiai töredékek nem egy harmonikus egészet jelentő részletek, hiszen nincs bennük semmi „eredeti”.

A vagina-szobrok felerősítik a többi hússzoborban is megbúvó undor-hatást, hiszen a néző olyan kontextusban találkozhat az abjekt-nek tekintett nemi szervekkel, melynek realitás-effektusa nagyon erős, ugyanakkor annyira bizarr, hogy a normális test-tapasztalatot is megzavarja. Nem egyszerűen arról van szó, hogy test-csonkokat látunk, hiszen a pornófilmek retorikája is a test feldarabolására épül. A hússzobrok vizuális határsértése a befogadási dichotómiák megzavarását célozza, de érdemes kihangsúlyozni, hogy elsősorban az élő és halott test közti ingadozás okozza a legelemibb élményt, vagyis az a sejtelem, hogy a szobrokat egy alapító erőszak teremti. Ez az erőszak azonban nem orvosi-klinikai eredetű. Gunther von Hagens plasztinált holttestei a klinikai értelem stilizált művei, melyek steril tökéletességükben mentesek mindenféle szubjektivitástól. Szöllősi hússzobrai azonban hangsúlyozottan barkácsművek és „házi” termékek, melyek épp ebből az otthonosságból merítik kísérteties személyességüket. Ez az intimitás válik annyira tolakodóvá, hogy a néző nem tudja magát függetleníteni tőle. De nem állíthatjuk, hogy itt a férfierőszaknak kiszolgáltatott női nemiség reprezentálódna, hiszen Szöllősi „munkáiban egy hagyományosan férfi tevékenységet (hentesmunka) köt össze egy nőivel (varrás), – a szexualitást neutralizáló, szenvtelenül melankolikus munkái éppúgy távol állnak a feminista, mint a szexista olvasattól.” Courbet poétikájától való radikális eltérés abban is megfogalmazódik, hogy a hússzobrok nem csupán meghívják-megidézik a vallomásosságot, hanem magát Szöllősit is bevonzzák a mű eseményébe. A Hús-projekthez készültek ugyanis olyan akciófotók (Action, 2005), melyeken a művész testi kapcsolatba bonyolódik „szerelmeivel”. A fotók egyszerre ironizálnak a szexista és a pszichopatológiai olvasatokon, de feltárják Szöllősi és a radikális peformansz-hagyomány közti kapcsolatot is. A látszat ellenére nem egyértelműek a mű és az alkotó közti hatalmi-érzelmi viszonyok. Courbet képe előtt állva – azt tekintetével leigázva – szituálta önmagát, de azáltal, hogy Szöllősi bemerészkedik a műbe, önmagát is kiteszi kép- és testtapasztalat azon bizonytalanságnak, melyet a hússzobrok jelenléte okoz. Az ambivalens hússal egybefonódva a saját test uralhatósága is megkérdőjeleződik, de épp ez Szöllősi poétikájának lényege: létezésünk megtestesült létezés, de a húsunk nemcsak a mienk, hiszen élőkkel és holtakkal egyaránt osztozunk rajta.

Nemes Z., Márió: Flash Art, Vol. I., No. 2, 2012, pp. 92, Budapest

Dora Sarvari: The Hungarian Barbarian

Tell me about your series of sculptures.

I made a series of 5 sculptures It is called “My Loves”. They are portraits. Portraits of girls I used to be in love with, girls who left me. I did not want to let them go so this is how I captured and preserved the feeling associated with them.

What are your sculptures made of?

Meat.

What kind of meat?

All kinds of meat mostly Beef and poultry. Also pork. I use a lot of tripe.

How much meat do you need to form a sculpture?

About 4 pounds.

How did you start working with meat?

Back in school we had an assignment. I had to make a self-portrait. I wanted to make a sculpture as real as possible. I was wondering what I should do, so that it would resemble the model as closely as possible. A model is a representation of something real. So mathematically it has to represent more than one aspect of it in order to look real.

Since it is a representation, no model can possibly include every aspect of the real world. If it did, it would no longer be a model. However, the more characteristics it includes the closer you get to what you wanted to achieve in the first place. After meeting one aspect, which is its shape, I was wondering what I could do to enhance the effect to make it as realistic as possible. I chose flesh to make my self-portrait. I found its effect in sculptural work uniquely human. It made sense to me to make a portrait out of what I am basically made of: flesh, meat.

Please tell me about your sculpturing technique?

It is quite simple, just like cooking and sewing combined together. I go to the market, buy some meat, go home, get out the pattern, cut the meat in shape, stitch it together, put it in a tank and fill it up. Then it’s all done.

Just like painters with their brushes or sculptors with their clay and stone I’m sure you have a relationship with the meat you use too.

What does meat as a medium mean to you?

I know it seems almost impossible to get around the spectacle of the material. Yet meat is not the center of my work. I feel the same about meat as everyone else. I do not have a special connection with it. I simply felt it was the right medium for these series of mine.

To me meat is just an effect, a tool. Meat takes me where I want to go. It is the channel to transmit my message to the viewer fast. With aggressive and direct art like mine, I felt that paint or stone is just not enough anymore in the 21st century. Or at least it’s not for me.

Do you consider yourself a shock artist?

No. Not really. I mean whenever anyone is trying to categorise my work I do fit in that box but only because of the aggressiveness of my art. I never even understood the concept of shock art or rather I don’t think that shock alone could be the answer. Let’s look at Marc Quinn, for example. One of his works is made of frozen blood. That does not make any sense to me. Meat does not have an identity. It’s just a piece of meat, simply pieces of a dead animal that I stitch together to form a female genital, but they become characters as I glue my personal belongings, little traces of personal histories to them. That is what makes them mine. That is what makes it art.

How do you deal with people turning their heads away or calling your work sickening?

I don’t take it personally. I mean my art does have an effect on the viewer, but isn’t that every artist’s dream? Don’t we all hope to touch the public emotionally? Even if it’s a negative reaction we get in return. I also don’t want everyone to like what I’m doing. I’m ok with people reacting differently. My grandmother, for example is used to what I am about. She lets me store my sculptures in her basement.

People who see your work associate you with what you do. Does that bother you?

I’ve come to realise that people are interested in who I am. They are unable to differentiate the artist from its art. That used to make me smile at the beginning, but now it rather bothers me. I don’t see why people who paint landscapes never have to answer such questions .Why does everyone assume that if you paint flowers you are a good, warm-hearted person while if you work with meat they think you must be some kind of a monster. I feel like I always have to explain myself, apologise for what I do. Over time, I’ve learned how to react to this. I try to make the best out of it. For example, when the ‘Lovers’ series came out, I heard people talking about it, saying that I use the sculptures for sexual purpose at home. So I made this series of photographs quite graphic and people can think I did it as an answer to those accusations.

What do you think is the reason for people to turn away and not want to look at what you do? Why are they so disgusted by and affright of what you do? What is it about meat that sets them off in your opinion?

I’m sure it’s not the subject of my work since that is something everybody can relate to: decay and fear of death, or in the case of my sculptures, the loss of love is something everyone is interested in. It is the material that scares them. They are unable to read between the lines. All they see is dead flesh.

I clearly do not understand people’s reaction. We are made of meat. If you turn away from it, you turn away from yourself. Maybe it’s because it reminds us of our own final destination. Of course it’s quite shocking. When I first started working with meat it made me feel uncomfortable as well. But how come it’s OK with us to watch movies where heads of people explode, kids are raped yet we are grossed out when seeing meat sculptures?

Even though they are affright of what they see they do look at your work.

Yes. I find it very interesting though, the fact that my art doesn’t stop with the object. There is a mechanism, which for a long time I was trying to define and understand. The viewers walk into the exhibition. Their eyes see something that looks like a dead body. They do realise after a few seconds that it cannot be a dead body since they are in an art gallery, yet their mind immediately makes them look at it as if it was a corpse. This game keeps my art alive. This vibration.

What is the message you are trying to transmit what are the questions you are trying to answer with your art?

I’m very much interested in body culture. We are often disconnected from our own insides. We don’t like looking at old or ugly people. Look at the covers of magazines. They display all these flawless women and men in there 20s. How hard people are trying to fight their age. It is such an obsession trying to look perfect. I’m trying to make people see that as well, even if it’s often uncomfortable for them.

This means the reaction of the public doesn’t influence you at all?

Not really. I am unable to do something different or even just something less aggressive. Why do I prefer making art that has shocking effect on people rather then pleasing them visually? Cuz I have always been like that. My work has always been too much. My life has always been imprinted with finding myself between extremes. If I started serving the needs of mainstream, that wouldn’t be me.

Metal magazine, 2009/2

Adele Eisenstein: The diary of a Taxidermist?

… In fact, it all began in 2003 with a simple assignment at the Academy of Applied Arts: to make a self-portrait.

In seeking the closest likeness to the human subject, and recognising that sculptures are most commonly made from materials that bear no resemblance to human flesh, Szöllősi found his solution in sewing together pieces of pork meat.

As he explains, it is, first, an extreme approach to the Aristotelian mimetic theory of art, secondly an interpretation of the scientific model definition, and, thirdly, it uses the working

mechanism of Christian relics.

The result, preserved in an aquarium of formaldehyde, is remarkably realistic. In the section of the show upstairs (with a warning that viewers should be over 18), a series of Szöllősi's My Loves

is on display.

Within the row of aquaria are graphic displays of female genitalia (and pelvises) rendered from combinations of pork and goose flesh, with labels indicating their names and countries of origin. Never spoke to him again

Szöllősi admits that though the relationship was already over when he got the inspiration to make the "portrait" of Min below the waist, after that she never spoke to him again.

But perhaps the most witty and hyperrealistic part of this project is the series of photos on the opposite wall, entitled Me and Her, in which Szöllősi leaves nothing to the imagination with respect to what he might do with his "loves".

The newest section of the Flesh Project series is Sexuality, in its Homo and Hetero versions. Yes, quite true to life. ...

The Budapest Sun/Style, 2007/2,

Dunajcsik Mátyás: Elefánt

Szöllősi Gézának

„A szép tanulmányozása párviadal, a művész

rémülten felkiált, mielőtt legyőznék.”

Baudelaire

– Tessék valami szépet csinálni belőle.

A kisfiú apró gombszemei úgy csillogtak, ... tovább

Győrffy László: Eleven hús

Szöllősi Géza kiállítása

Körzőgyár, Budapest 2007. január 31 – február 24.

Pedro Almodóvar 1997-es filmjének a címén kívül nincs sok köze Szöllősi Géza kiállításához, ahol a húsban rejlő szenvedély megdermed a 15%-os formaldehid-oldatban, s míg a film dramaturgiája kivezet bennünket a Franco-korszak poklából, addig Szöllősi produkciójában a diktatúrák anti-esztétikáját a fogyasztás diktatúrája váltja fel, egyedül a politikai korrektség börtönéből kínálva szabadulási lehetőséget. E nagyszabású bemutató a művész eddigi, gyakran felháborodással kísért, ötéves pályafutását hivatott összefoglalni, próbára téve azon nézők látóidegeit, akik a budapesti szcéna ingerküszöböt alulról súroló kiállításain szocializálódtak. Az új kiegészítőkkel felülstilizált hússzobor-sorozatot a Taxidermiából átmentett, burjánzóan pszichedelikus víziók színesítik – kisebb csoda, hogy mindez egy kereskedelmi galéria, az Octogonart égisze alatt kerül bemutatásra, annak lerakatában, a Körzőgyár hűvös termeiben. A poszt-indusztriális hely szelleme a Nőmérő tábla című objekt felületén körvonalazódik újra, amely már a Filmszemlén díjazott új Szász János film, az Ópium látványterveiből önálló életre kelt projekt része, a Csáth Géza írásokból derivált elmegyógyintézet miliőjét töltve meg pluszjelentéssel. Az elmegyógyintézet fogalmát természetesen kiterjeszthetjük nagyobb közösségekre is, melyek kollektív tudatát az alkotó egyenesen printjei fémes felületére vetíti: a 20. század gyalázatos szakaszainak obskúrus manipulációi keverednek a cyber-korszak lehetséges testdeformáló megoldásaival, kisebb idővihart kavarva a digitális interface semleges közegében. Szöllősi mutáns vírusoktól begerjedt szoftvere felülírja az eddig érvényesnek hitt fájlokat, bebizonyítva, hogy az emlékeink mind hamisak, a jelképek pedig éppúgy felcserélhetők, mint testrészeink: „Az Ember széttört képmása nyomul előre mindenütt percről percre, sejtről sejtre… A szegénység. a gyűlölködés, a háború, a rendőrbűnözés, a bürokrácia, az őrület – ezek mind-mind az Embervírus működésének tünetei” (William S. Burroughs: Meztelen ebéd). Nem kétséges, hogy Szöllősi Géza az Interzóna kettős ügynöke, tudatmódosítóként ható alkotásai súlyosságuk ellenére folyamatosan lebegnek abban a határtartományban, amely összeköti a zsigeri valóságot a high-tech fikcióval, a szervest a műanyaggal, az elevent a halottal, az Amerikai nő és a Kínai szépség között félúton egy olyan megmagyarázhatatlanul abszurd régió felett, amelyet nevezhetünk akár Magyarországnak is. Szöllősi ebből a pozícióból, kellő empátiával és szarkazmussal felvértezve tett kísérletet a platóni mimézis-elmélet legextrémebb megközelítésére, akváriumban úszó, állati belsőségekből varrt nemiszervekkel emlékezve meg Szerelmeiről, miközben a szexuális kiszolgáltatottságot szublimáló Suzuka-babás print sorozatában önreflektív módon elemzi saját művei hatásmechanizmusát. A létezés minden rettenetét felmutató Hús-projekt indukálta érzelmek tartósak, sőt, örökérvényűek; a profán relikviák legfrissebb darabja (Hetero-vaginál) a húsbotrányok elkerülése céljából EU-s bélyegzőt is kapott. Ebből is látszik, hogy Szöllősi megfelelő anatómiai ismeretekkel rendelkezik a társadalom felépítéséről ahhoz, hogy annak gyenge pontjaira célozza precízen kimért ütéseit: a preparált kisállatokat csatasorba állító csocsóasztal (Hörcsögök vs. Mókusok) nem kegyetlenebb, mint a high-society mintafeleségeinek szőrmebundái, a Nőmérő tábla pedig mívesebb és szórakoztatóbb, mint a szexközpontú nőmagazinok fasiszta hirdetései. Végül is már napi rutinprogram, hogy önként sétálunk a húsdarálóba: a Disznó disznónak farkasa című installáció önnön kolbászaival küzdő kitömött malaca tökéletes makettje az önpusztítás (emberi) természetének, egy mítoszától megfosztott, nevetséges Laookón inkarnációját állítva reflektorfénybe. A kiállítás legkülönfélébb médiumokat felsorakoztató, reneszánsz diszharmóniája leperget magáról minden eddigi kategóriát, hiszen maga Szöllősi Géza sem egyszerűen képző- vagy fotóművész vagy filmes látványtervező, hanem a kortárs magyar vizuális kultúra lelkiismerete, aki még időben szólt közbe, hogy provokatív költészetével elvégezze helyettünk az elmaradt önvizsgálatot.

Géza Szöllősi is a skilled multi-disciplinary artist working in a wide variety of mediums including taxidermy, animal flesh, photography and graphics. He worked as designer in several award-winning Hungarian films like Opium and The Notebook and Taxidermia.

Géza's artworks has been exhibited alongside artists such as Jake and Dinos Chapman, Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman in the 'Decadence Now! Visions of Excess' organised by Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague. His work is held in collections in Miami, New York, Seoul, London, Prague and Budapest.